PREFACE

Starting to write this story I find myself surprised at what I'm

about to do. That it's being written at all is in itself amazing.

I never intended to write about my memories and recollections

of the period served in combat during World War II.

It was a period of my life that had been put behind me to be forgotten.

- Too ugly to be remembered. Too unimportant to anyone but myself

and the others who went through it; until a stranger, two generations

younger, came along and convinced me of the importance of what

I had experienced and why my recollections and memories of those

experiences should be shared with others, in the name of history.

In the part of this story where the email exchanges between Kent

Cooper and I are quoted, our initials precede the actual quotes,

e.g., 'JM:' or 'KC'. An extra line of white also separates these

exchanges.

Some names have been changed to protect the actual people. I have

also avoided giving the names of most persons to protect the families

of those who are no longer with us. Kent Cooper's name is shown

with his permission.

Jerry McConnell

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

On December 7, 1941, World War II began. The United States had

tried intensely to stay out of the turmoil that had enveloped

Europe, the Middle East and the Far East.

The state of international communications back then was not nearly

as sophisticated and efficient as that which we enjoy today. Radio

transmissions were probably as swift as our current methods but

accuracy and control of signals were not dependable. If the aircraft

of that period were described as flying on a wing and a prayer,

radio communiqués would certainly be dubbed as being sent

with crossed fingers and silent prayers.

Newspapers usually carried stories of wartime events several days

or weeks after its happening. Of course, television was still

in the distant future, and radio newscasts were nearly as delinquent

in reporting as the newspapers. One of the great sources of visual

news was the Fox Movietone News film clips shown at local theatres

between showings of the feature attraction movies. Another famous

visual carrier of news events was the March of Time, which told

a more detailed story of the events.

It was difficult to get public interest piqued about a particular

battle or combat engagement because most people knew that what

they were hearing or seeing had probably happened some time before

and that it was likely not even news any longer.

Consequently, the wars and battles being waged in far off places

seemed much too remote to bother most Americans. Except in high

level strategic intelligence circles of the military and affected

government agencies, the great majority of the American people

were content to let the Germans and their European neighbors and

the Japanese and the other nations of the Orient battle it out

without any interference from us. That is, until the Japanese

bombed the American naval fleet docked at Pearl Harbor in the

Hawaiian Islands.

Though not then a part of the United States, the Hawaiian Islands

were under our protection and the blow dealt to our naval fleet

could only be answered with a formal declaration of war. And suddenly,

it was no longer just the Europeans and Orientals at war; we had

joined the trial.

I had the honor and privilege of serving my country during World

War II as a member of the finest military organization in the

world, the United States Marine Corps. I was only seventeen years

old and in my senior year in high school on December 7, 1941,

when Japan decided to bomb Pearl Harbor. War was immediately declared

between the two countries and thousands of young American men

headed to the nearest military recruitment office to enlist in

their favorite branch of the service.

In that an older brother had been in the Navy for a few years,

that was where I wanted to be. Even before the war had begun,

I decided to join the Navy and had actually tried, but was turned

down because of a deviated nasal septum, a minor nose problem

I was never aware of, but the Navy took exception and refused

to accept me. The Navy recruiter knew that United States entry

into the war was only a matter of time and not wanting to lose

a potential recruitment told me that he was going to "consider

me as a, sort of, reservist waiting for assignment."

I was later told that this was merely a 'line' that some recruiters

used to hang on to possible enlistees rather than lose them to

another branch of the services. I also wrote to my brother in

the Navy and he told me that same thing, that I was not a reservist

and under no obligation whatsoever to join the Navy. In fact,

he very vigorously advised me to wait until I was drafted as I

might stand a better chance of not going overseas than if I enlisted;

advice I was not planning to honor.

When war was officially declared on December 8, 1941 I met with

several of my school chums who had talked about the service and

felt as I did, and as a group of seven we decided to enlist. My

early plans to join the Navy were discarded when after much discussion

and debate we unanimously chose the Marine Corps. A day or two

later when we went to the recruiting station to just talk with

the recruiters, we were given the full treatment about the difficulties

of military life, the Marines in particular, but what a satisfying

experience it would be to suddenly be converted from little acne-challenged

teenagers to adult young men.

After the grand pep talk and getting us all geared up to sign

up right that day, in spite of needing parental permission, we

were all subjected to a partial physical examination and inquiry

as to our physical well being. We were all turned down for one

reason or another; an unbelievable seven out of seven.

My old nemesis, the deviated nasal septum, was still in my way.

Others had, among other things, underweight, punctured eardrums,

overweight and flatfeet. All of us were told to go home until

after the Christmas and New Years holidays then come back in,

as the recruiting stations would by that time have received new

and more tolerant minimum physical standards information. Though

disappointed, we were encouraged by the recruiter to hold out

and become Marines, a decision we'd never regret.

The next few weeks was a period of confusion, indecision, mind-changing,

pressure from friends not to go as well as families that were

nearly unanimous that we were making a big mistake.

My brother who was already in the Navy was coincidentally back

from a shipboard tour of duty in the Mediterranean and was given

leave for Christmas. He had been in the service for a couple of

years at that time and I guess he just didn't want to admit that

his little brother was going to go off to war; especially with

the U. S. Marine Corps!

In that my mother had to sign a release of some kind, (I was only

seventeen) my brother kept prodding her to not sign the papers.

My response was that I would be able to go without her signature

when I turned eighteen, which was only a few months away, and

I would go then anyhow. I argued that if I were to go now, I might

be given a better assignment than if I waited until many, many

more young men would be going into the service. I might even have

a choice of what kind of an assignment I would get. A hope and

a prayer that didn't turn out that way at all.

On January 5, 1942 I went alone to the Marine Corps recruiting

station as one by one the others who had gone with me to the recruiting

station initially had changed their minds (or perhaps it was their

parents who changed their minds;) this time an unbelievable six

out of six. The new physical standards now permitted us physical

degenerates with deviated nasal septums to serve our country.

But another problem had cast its ugly head and darkened my departure.

I was a few pounds underweight. After getting over that problem

by going to the nearest market and buying and consuming a large

amount of bananas, and then just barely meeting the minimum weight,

I was accepted and on my way to becoming a Marine!

I spent the next nine weeks in basic training "boot camp"

at Parris Island, South Carolina, shortened from the normal twelve

weeks due to wartime exigencies, but made up by much longer days

and nights and absolutely no time off whatsoever. Boot camp in

the Marine Corps is where you either become a Marine or spend

the rest of your life in humiliation. After many points of pain,

fear and degradation I surprised myself and my doubting Navy brother

and succeeded in making it through the abominable ordeal.

On completion of that tour de force I found myself stronger, healthier,

heavier and much, much smarter, if not in patent gray matter,

but certainly in self-preservation, I was graduated into the newly

formed infantry organization, the First Marine Division. A name

that has been, and still is, synonymous with the elite of world

military organizations.

For the next three months from early March 1942 until early June

we were pounded and rounded into a fit and ready fighting machine.

Most days began around 4:30 A.M. and ended in early evening, although

several nights each week were also devoted to night maneuver training

which usually extended the day until about midnight, and occasionally

later. Then it was crawl back into bed only to be wakened again

around 4:30 A.M. to start it all over for another day.

Growing up I had fired B-B guns and twenty-two caliber rifles

on hunting trips with my next door neighbor friend and his older

brothers. I had even fired a twelve-gauge shotgun, so I was not

unfamiliar with weapons. We had learned the basics of rifle and

pistol firing in boot camp, but here we honed those skills to

a sharp edge and eye. We also learned the niceties and finesse

of using Thompson submachine guns and Browning Automatic Rifles,

both much faster and heavier in firepower than the standard issue

Remington thirty caliber, single shot, bolt action rifle; things

that would be needed later as we forged our way in the jungles

of the South Pacific.

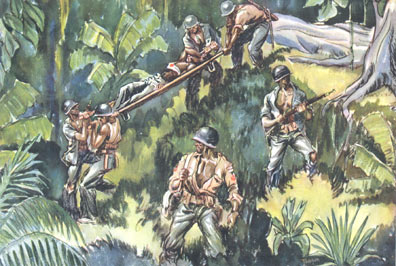

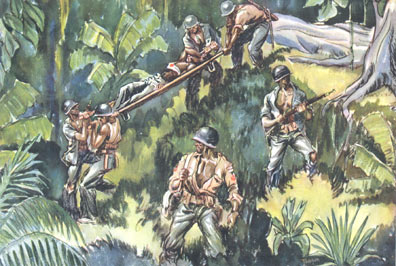

Also during these short training-intensive weeks with the long

days, we were taught the fine art of man-to-man combat while using

a bayonet fixed in place at the business end of our rifles. We

heard the commands, "lunge, parry, thrust" hundreds

of times during those days as we fended off simulated enemy bayonets

and stabbed the bayonets into stoic and unsmiling straw dummies.

Our earlier school experiences in athletics helped us to pitch

and lob, first unarmed, then later live, hand grenades into and

on to targets with little or no visual sightings. We learned how

to crawl on our bellies with full combat gear under barbed wire

strung only inches above the ground as live rounds of rifle and

machine gun fire zinged and whistled just barely over our heads

and bodies.

Retired and recalled to active duty Marines gave us the benefit

of their knowledge of jungle fighting they had experienced in

Nicaragua, Haiti and other Caribbean islands. They showed us how

to use our bayonets as hand weapons for hand-to-hand knife fighting

when needed as a last resort. These sessions were always surprising

to us as we expected these older, retired men to be a bit soft

and a step or two slower in reaction. We found just the opposite

to be true. They were amazingly agile and cobra quick.

By the end of May when we got orders to pack up and be ready to

move out, we were lean and hard and spoiling for a good fight;

something we would get sooner than expected. Earlier that month

two of our regiments had gotten orders to sail off in the direction

of the South Pacific. Each regiment had taken a different route

of departure and a different time with different destinations.

We later learned that the Fifth Marine Regiment had sailed by

ship to Wellington, New Zealand and our Seventh Marine Regiment

left also by ship for American Samoa. We would in due course be

reunited with the Fifth, but the Seventh would be held in Samoa

for nearly six weeks before it would rejoin us.

In early June the First and Eleventh Marine Regiments and other

special support units which comprised the bulk of the First Marine

Division, boarded a troop train that wound its tortuous way across

country to San Francisco. The trip was very boring and uneventful

except for one stop in Elko, Nevada where we were greeted trackside

by none other than Bing Crosby one of the most famous singers

of that period. He was not there to sing for us but he went to

just about every Marine he could reach during our brief stay to

take on provisions and water just to shake our hands and give

us his best wishes. His wife Dixie Lee accompanied him on his

rounds and also shook our hands.

Our next stop was San Francisco where we were finally allowed

some shore liberty and of course, knowing we would soon be leaving

for God knows where, we tried to make sure that all of the beer

and liquor in San Francisco was consumed. My big event at that

stop was during a trip across a large parking lot with one of

my buddies en route to another 'watering hole', when we encountered

this very lovely looking woman with an equally lovely looking

young female friend.

In the process of trying to "pick up" this delectable

pair, we discovered that it was none other than Harriet Hilliard,

the wife of famous band leader, singer and actor, Ozzie Nelson.

Her friend was just that, a friend. When she explained who she

was she offered to have us come to the theatre where she and Ozzie

were appearing at 8:00 P.M. that evening to see and hear their

show. She told us to just ask for her and she would see that we

were admitted at no charge and would be holding very good seats

for us.

However, after finally making it to the 'watering hole' (I still

remember the name of the place, "The Pirate's Cove",

and I often wonder if it is still there) we began to do our part

in making sure San Francisco was left "dry". My buddy

and I were more successful at scoring with the female population

and our total attention was directed toward the two companions

we had corralled.

We left the Pirate's Cove and began to move on to other equally

enjoyable alcohol establishments with our newfound friends and

didn't realize the time until around midnight when two Shore Patrol

MP's decided that we had had enough and should be on the way back

to the ship. They very graciously even drove us to the ship (I

believe it was to make sure we didn't get lost in another 'watering

hole' or the girls' apartment on the way.)

Neither of us, and we had a lot of company, made it to our bunks

and we woke up the next morning aching and sore from sleeping

on the hardwood decks. Our heads were also aching and sore, but

we had done more than our share towards depleting San Francisco's

alcohol stores.

We finally got under way when the ship departed for an unknown

(to us) destination on June 22, 1942. It was called a ship only

because it could float. A sludge-carrying scow could sooner be

classified as a ship. It had little resemblance to any military

vessel ever seen before. More gory details about this painful

and punishing trip are provided later concerning the USS Ericcson.

We did eventually find out that we were headed for New Zealand

and subsequently, a tour of wartime combat for which even the

Marines weren't fully prepared and hadn't expected in its sheer

brutality and degradation to mind, and body.

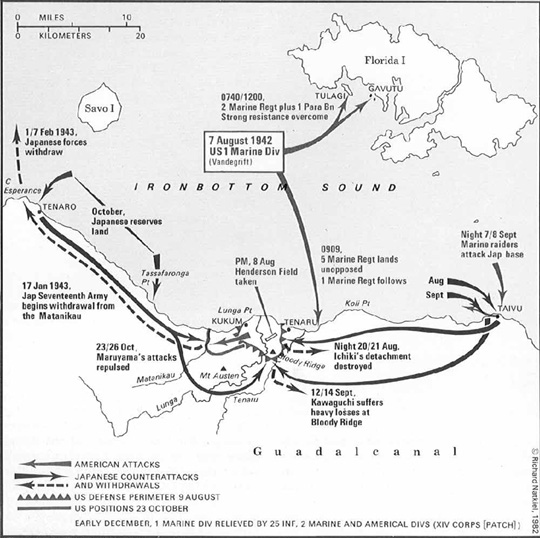

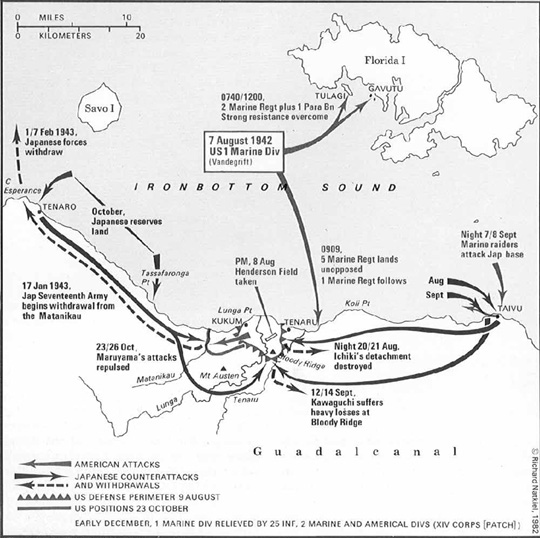

The Marine spirit however, was never injured and that was what

saw us through the campaign known as Operation Cactus - the invasion

and recapture of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, from the Japanese

from August 7, 1942 until finally relieved and placed on transports

departing on December 15, 1942.

Fifty-four years later in 1996, I was browsing my way around the

latest phenomenon - the Internet, with my computer. In one area

of the "Net" I found a message bulletin board for military

inquiries where one could try to track down long-lost friends

who had military connections. I posted a message inquiring as

to the whereabouts of one of my best friends who had served with

me on Guadalcanal while in the Marine Corps. I asked if he or

anyone who might know of his whereabouts could please respond

to my email address.

After a week or two had gone by and I had mostly given up on seeing

anything in the way of a response, an email message was received

from a young man named Kent Cooper. Kent apologized for not responding

about Jocko (the nickname of the friend I was trying to locate)

but because he had a great-uncle that had also served with the

Marines on Guadalcanal he decided to ask me about any possible

connection I may have had with his uncle.

For the next several weeks we exchanged email letters on the subject

of Guadalcanal. He asked questions about the campaign there that

brought back my all too putrid memories of that place. I would

respond as best I could from a memory bank that was more than

a half century old and not opened for many, many years. He told

me of his personal visit to the island a few years prior to his

writing to me and brought me up to date on current conditions

including the political climate that prevailed there.

In one of his writings he made a statement that made me think

twice about all on which we had corresponded. He made me realize

two things, 1) That what I had experienced on Guadalcanal was

historically important, and by today's standards, was on the verge

of becoming ancient history; and 2) It should be written down

in my words as it happened to me while I was there. He stated

that I "was an eyewitness to history" and I should make

every effort to preserve my recollections.

The sincerity of that exhortation struck me in a way that had

never occurred to me - that someday, somewhere, someone, would

be interested in reading about the World War II battle that turned

the tide against the Japanese aggressor and won the war for the

Allies from a first-hand account of one of the Marines who was

there from Day One.

With some thought as to how it should be done, came the realization

that much of it already done and residing in the numbers of emails

we had sent and received in the computer's data banks. All that

was needed was to assemble the pieces of correspondence from Kent's

first email asking for information, to the last bit of it provided

to him by me. As you'll note, the questions he asks are pointed

and pertinent.

They are questions that probe into areas not thought of, or at

least never asked, by reporters. They aren't the canned, usually

expected questions such as the anemic, "What was it like

over there?" which I have been asked by not only reporters,

but also average people. Sure, it's a generic question, but it

doesn't indicate any specific interest, just general, overall,

blanket-type interest.

Students in grades below the high school level get point-blank,

on-target interest when they ask, "How many people did you

kill?" or "How did you feel the first time you had to

kill someone?" Those questions show a definitive interest,

albeit slightly morbid, but not unexpected from young people.

You know the saying, "Out of the mouths of babes ..."

So with most of the work already done for me, save for editing,

adding, deleting, dressing up the language and pulling all of

the letters together, what follows here is my first-hand account

of the battle for Guadalcanal, covering the period of my residency

there, August 7, 1942 through December 15, 1942 and some post-combat

recollections as well. Needless to say, I'll never be able to

adequately thank Kent Cooper for his instigation and in-depth

inquiries, which made it all possible. This May - November, multi-generation

span between the inquirer and the inquiree cast a spotlight on

the need for the truthful corroboration of an event of historical

significance that was enacted more than a half century before.

An event that had caused a great void in the mind of a young man

of today; an event that had been tightly closed in the deepest

recesses of the mind of an older man who was, the eyewitness.

CHAPTER TWO

The Beginning

KC: 6/30/96, (Kent Cooper's first email):

"Mr. McConnell:

"Noticed your posting on the military bulletin board. Sorry

to say I'm not responding about Jocko; just wanted to ask you

which unit you served in.

"In 1992, I lived on Guadalcanal for six months retracing

the steps of a great uncle who was with the 5th Marines. I lived

at Red Beach, right where he landed, about 20 km east of Point

Cruz. If you're up for it, I'd love to share some observations

about Guadalcanal today. Would also like to ask you about your

experiences there. I've studied the battle for a long time and

I think it ranks up there with the great epic military struggles

in history -- like Waterloo and Gettysburg.

"My hat is off to you, sir, for what you did for my country.

As an American, I thank you.

Semper Fi. Kent"

JM: 06/30/96

"Hi Kent,

"Thank you for the kind words, and yes, I agree with you,

Guadalcanal was an epic battle in spite of many historians not

recognizing it as such. One thing that is almost always overlooked

is the fact that it was the first major Allied land offensive

of World War II. Most articles I've read acknowledge that it was

the turning point of the war against Japan, and even some that

will state that it was the first large encounter against Japanese

land forces, but I have yet to discover the historian/writer that

realizes and states that it was the first major Allied land offensive

of World War Two. This could be true because of a lack of interest

or it may be the lack of desire to do the actual research necessary

to establish this fact.

"I did a lot of research before I came up with that conclusion

and it has been suggested to me by some that the North African

campaign was the first, but the North African offensive movements

against the Germans were not of a major scale until after August

1942 when the Guadalcanal campaign began.

"To be sure there were battles fought before August 1942

in various places, but they were mostly of the defensive nature

and any offensive movements were mainly raids and skirmishes not

of large scale. I have never really pursued it with anyone because

whatever has or has not been said about it, at least I am aware

of its uniqueness.

"The First Marine Division was formed in 1941 in Guantanamo

Bay, Cuba; out of what had been the First Marine Brigade. After

enlisting on January 5, 1942 and spending the next nine weeks

at recruit training Boot Camp in Parris Island, SC, I was assigned

to the First Marine Division's, First Marine Regiment, 3rd Battalion,

'K' Company.

"We were bivouacked in New River, NC, at a temporary tent

camp on the site of what is now Camp Lejeune, NC. This was in

March, 1942, along with the Fifth, Seventh and Eleventh Marine

Regiments. Later that same month the Seventh Marines were detached

from the Division and they left in early April by ship convoy

from Norfolk, VA to the Pacific area.

"At the time we had no idea of why they were detached nor

why they were sent alone to the Pacific. Actually we didn't even

know that they were headed to the Pacific area, but we knew it

was in the general direction which had been the undeviating direction

of the Japanese forces. And, when they raided the other regiments

for senior NCO's and officers to completely fill their ranks,

we speculated that they would be going into combat against the

Japanese before any of the rest of us. Time would prove the incorrectness

of that assumption.

"In mid-May, 1942 the speculation again ran rampant concerning

destinations when the Fifth Marines sailed out of Norfolk, down

through the Panama Canal and on to New Zealand. Were they going

to join the Seventh Marines to form a combat group to engage the

Japanese? Or were they going their own way into a theater of combat?

"Then finally in June the First and the Eleventh Marines

closed their training sites in New River and we proceeded west

across country by troop train and then departed the States by

ship from San Francisco on June 22 bound for New Zealand. Were

we at long last to be reunited with our fellow regiments from

the First Marine Division somewhere in the South Pacific and join

in the battle with the hated Japs?

"Our guesses were only partially right. We did rejoin the

Fifth Marines in Wellington, New Zealand. Then about three weeks

later we left by another ship, this time the USS McCawley , a

regular US Navy ship, to engage the enemy but it was without the

Seventh Marines who had been dispatched to American Samoa and

who were unable to join us for the landings on Guadalcanal because

of a severe scarcity of troop transport ships. They would not,

in fact, join us for more than a month after we had landed on

the island.

"Our first real excursion into war started off in a manner

that should have told us that life was not going to be much fun

for a long time. The troop ship that carried us was named the

USS John Ericcson. Most of us called it either the "floating

coffin from hell" or the "diarrhetic disaster"!

"There were seven thousand of us on the dirtiest, poorest

equipped, rottenest vessel, with the most vile-tasting and absolutely

spoiled rotten food of any garbage or scum loaded scow that ever

to put to sea.

"The food, if you could call it that, was so poor that most

of the Marines chose not to eat it. During the twenty-day trip

from San Francisco to Wellington, New Zealand, the only food that

was edible was what we could buy from the ship's stores: candy

bars, cans of Planters peanuts and bottles of Pepsi.

"After the first few days of that diet, diarrhea caused long

waiting lines at the ship's heads (toilets) and almost stem to

stern decks covered with vomit of expelled peanuts, candy and

Pepsi. The only positive note that came of the siege of stomach

and bowel problems was the constant hosing down of the decks.

It was probably the cleanest that ship's decks had been in decades.

"To be fair, the ship was a contract vessel, not U.S. Navy

we were told; but the crew on board dressed like sailors and were

very disdainful of the Marines not to mention contemptuous because

of the condition of the decks and heads. They, through their own

laziness, ineptness and total lack of discipline amongst the ship's

officers and crew caused the problems of poor sanitation and spoiled

food supplies, but they refused to accept the resultant dirty

and unkempt conditions as their responsibility.

"Nearly every Marine lost upwards of 10 to 15 pounds and

was in poor physical condition during the course of the voyage

to New Zealand. This and the subsequent abandonment of the Marines

after landing them on Guadalcanal with less than half of their

food, supplies and equipment cast a very dark cloud over the U.S.

Navy in the minds of the Marines for a long time.

"The eagerness of the Marines to save sailors that swam ashore

after having their ships blown out from under them during the

ferocious naval battles in the bay just off the coast of Guadalcanal

was enigmatic. But our debilitated physical conditions hadn't

deteriorated our minds to the point where every sailor looked

like those on the Ericcson or Admirals King, Fletcher or Ghormley,

the navy commanders who made the decision to abandon us on Guadalcanal

and hightail it for their own safety.

"These guys washing up on shore were just more of our countrymen

and we did everything in our power to help them.

"The original plan was for the First, Fifth and Eleventh

Marines to stay in New Zealand for several months and the Seventh

to rejoin us there. The new orders to recapture Guadalcanal Island

changed everything.

"The day we sailed into Wellington harbor the weather was

mild and calm. The sight of that port after the living hell we

had experienced on the Ericsson for the previous three weeks looked

to us as the portals of heaven must look to new entrants.

"No one escaped the debilitation of the dysentery and diarrhea

that was suffered on the voyage from San Francisco. Wellington,

New Zealand went a long ways to make us spiritually, if not physically,

repaired.

"The calm water reflected the beautiful rising hills in Wellington.

But even before we had docked, word came down from higher headquarters

that there would be no liberty in New Zealand. Furthermore, all

hands were restricted to the ship to assist in the unloading of

our equipment and supplies and then reloading that plus more equipment

and supplies onto the USS McCawley and a dozen or more other ships

that would be traveling with us.

"Almost simultaneously with that bad news came the first

of many torrential tropical downpours that would plague us for

the next two weeks. Handling thousands of tons of supplies and

equipment off certain ships and on to others in driving rainstorms

did little to help either our physical conditions or morale. Literally,

tons of foodstuffs were ruined because of the inability to get

the cardboard cartons out of the downpours. The docks were undergoing

another disruption by the dock-workers and stevedores of New Zealand

conducting work stoppages and walkouts during the most critical

times of the project.

"Conditions couldn't have gotten any worse than they were

during those dark and dreary days; yet in the coming months, there

were to be many occasions when we wished for the relative serenity

of the New Zealand docks, because things were so direful and seemingly

hopeless.

"The First, Fifth and Eleventh Regiments reinforced with

Raider battalions and other special units sailed from New Zealand

less than 3 weeks after we arrived and headed for Guadalcanal,

Solomon Islands, a place that at that time, to my knowledge, was

unknown to anyone aboard.

"Though we were happy to get away from the downpours of New

Zealand, and the surly, arrogant attitude of the dock-workers

we weren't at all sure about what it was we would be facing. Oh,

we certainly knew that we were headed for some combat; and we

were told that the Japanese soldier was a fierce, shrewd and cunning

competitor. It was just something that we didn't need right at

that time when we were still debilitated and run down from the

exhaustive trip from San Francisco.

"We were told that the Japanese soldier liked to do his fighting

at night. That he had eyes like a cat and he was just as quiet

and secretive about his movements. We later found all of this

to be true. But one other thing we were told that also turned

out to be true was that even with our outdated (mostly World War

I) equipment, we were better and smarter fighters. We also found

out that the Japs seldom followed up on opportunities which arose

that could have solidified their stranglehold on the entire island.

They often waited too long to seize the initiative after a particularly

devastating air raid or naval shelling. That weakness allowed

us to regroup and be ready for their next moves.

"As we made our way to the Solomon Islands there were day-long

information and training sessions about the enemy we'd soon encounter

and that the long days and nights beach landing training we had

received in North Carolina would be put to the test on our first

contact with him.

"There had been a side trip from the run to the Solomon Islands

scheduled to the Fiji Islands where we were to get in some practice

landings, but the tactical information that had been furnished

to our commanders failed to state that the beaches that looked

so good from a distance were, in fact, laced with sharp coral

which would have torn open the bottoms of the boats we were to

use. Had this happened, the scheduled landing on Guadalcanal would

have been delayed. So the practice runs were canceled and we resumed

our course.

"Then on the morning of August 7, 1942, after several hours

of air and sea bombing and shelling of the beaches, my unit the

First Marine Regiment landed on Red Beach in the second wave,

behind the Fifth Marines. We caught the Japs completely by surprise.

In fact, in the encampments we passed through, warm bowls of rice

and oats were still on their breakfast tables and small fires

were plentiful where water was being heated or boiled for washing

or morning tea.

"Our intelligence information had accurately estimated the

strength size of the troops there to be approximately two to three

thousand, with another thousand or so workers, mostly captured

Korean soldiers from other battles. All of them grabbed what little

they could carry and bolted off toward the hills and jungles of

the island.

"Our landings were mostly uncontested by the Japs, except

for an occasional sniper who would fire a few rounds from his

rifle and then run to another location and try to do the same

again. There were few casualties as a result of these snipings,

but their presence delayed our forward movements. One lonely sniper

could stall the movement of a few thousand men until he could

be located and blown out of the tree he inhabited.

"My unit, the Third Battalion of the First Marines, was given

the objective of capturing a large grassy knoll just to the south

side of the airstrip that butted up against the mountains. The

Japs had used it as a reconnaissance point to watch over the airstrip

as it was being constructed. Possession of that high ground would

likewise assure the safety of our forces down at the airfield

after we had taken possession.

"At that point in time, we were still under the belief that

our aircraft would soon be making landings on that airstrip. Little

did we know that our own Navy would soon be deserting us and leaving

us with less than half of our food, supplies and equipment unloaded.

I'll go into more detail later about the tortuous trip to that

grassy knoll.

"Did you go to Guadalcanal for the 50th anniversary celebration

Kent? I would have loved to have been able to go there but I didn't

even know about it until a couple of years later. I knew some

of the guys in the Fifth. What was your uncle's name? I lost a

friend that went there with the Fifth.

And yes, I'd be happy to exchange notes and views on this subject.

Write whenever you can. Jerry"

KC 6/30/96:

"Mr. McConnell:

"Thanks so much for the response. I think people who really

study the entire war, who keep a macro perspective on what the

Pacific was like in 1942, will almost certainly come to the same

conclusion. William Manchester and Richard Frank are two authors/historians

who leap to mind as examples. Don't know if you are familiar with

Manchester but he is a terrific author and a Marine himself, a

veteran of Tarawa and Okinawa no less. Here's what Manchester

had to say about Guadalcanal in an Op-Ed piece published in The

New York Times on August 7, 1992 -- the 50th anniversary: 'Bastogne

was an epic in Europe: the 101st Airborne was surrounded for eight

days. But the Marines on Guadalcanal were isolated for four months.

By October, the typical leatherneck had a malarial fever and open,

running sores (jungle rot). He wore stinking dungarees, had been

reduced to eating roots and weeds and had lost 25 pounds...'

"Manchester, a noted author and emeritus professor of history

at Wesleyan University who had served in the Marine Corps from

1942 to 1945, stated that even General Douglas McArthur thought

'the Marines survival was open to the gravest doubts'.

"Manchester added that 'the Army Air Corps refused to send

aircraft there; the crews of merchantmen bearing food for us refused

to sail there; the senior admiral in the Solomons refused to strengthen

the force there. The Marines were written off - doomed.' (JM Note:

In truth, many of us never expected to see home again. But we

never stopped fighting. We never gave up. We were Marines.)

"He finished the article thus: '...But to me that struggle

was more than a strategic victory. It was, and is, eloquent testimony

to the fortitude of man. Men generally do what is expected of

them; usually that is very little. On the 'Canal they were asked

to do what was believed to be impossible, and the shining response

of those Marines on the line is historic. I shall never forget

them, nor should you.'

"My great uncle was PFC David K. Massey of Ashwood, Tennessee.

Your chronology of events when he shipped out is spot on with

my research. He went through the Panama Canal to New Zealand,

then to Guadalcanal through Fiji. He was in the first wave at

Red Beach."

JM: 7/1/96

"Kent,

"I read Manchester's "Goodbye Darkness" and was

very much impressed. For him to say what he did in the Op-Ed piece

in the NY Times is high praise coming from someone who went through

all that he did. It is really humbling. It made me feel as though

I had done something well above the normal call of duty. Yet,

as I did it, I felt no special importance or great sacrifice.

My country had sent me there to perform a service and that was

what I had enlisted to do. I did what I felt I had to and what

I was ordered to do. Even later when I realized a bit more about

the significance of that particular battle, and how fortunate

I was to survive what seemed like a doomsday scenario, I felt

no special, nor heroic feeling.

"He so accurately described our situation that it brought

back vivid memories. For nearly the entire time there we didn't

have any sheltered places to sleep at night. A poncho over a foxhole

dug in the ground was about the best we could manage. Finally

the last week or two as more and more ships came with Army troops

and supplies, there were tents erected and wooden cots furnished.

"After sleeping on or in the ground for about four months

we almost had to learn how to sleep in a cot again. As for bathing,

during the first 100 or so days, it was a rare luxury we could

only dream about.

"There was no place where we could go for a respite from

the constant action. The entire three by five mile perimeter we

occupied was all front lines. The occasional sneak off to a very

close-by river to jump in, clothes and all, and to wash away the

grime and stench was pure heaven! Unfortunately, after an hour

back out in the heat and humidity, it was back to reality and

we didn't even notice how badly we reeked.

"I weighed around 150 pounds when we left San Francisco in

June and what I lost on the trip to New Zealand, fifteen to twenty

pounds, I never regained before we hit the 'Canal. The long grueling

working conditions in New Zealand, coupled with less than desirable

meals and lack of sleep probably added to the weight loss instead

of the reverse.

In the months that followed, the malaria, dysentery, and jungle

rot continued to hammer away at what was left of my skinny frame.

I was at my lowest weight of 115 when we arrived in Australia

in December 1942.

"The USS Ericcson, the rains, non-stop work with very little

rest and sleep in Wellington and then finally, four plus months

on Guadalcanal reduced me to little more than a shadow.

"I didn't know David, but that's not to say that our paths

didn't cross at some point during that ordeal. As I mentioned

before, a school chum from my hometown (Altoona, PA) was in the

Fifth Marines and we visited occasionally when our units were

close enough for walking. So who knows? David could have been

around on those times when I visited the Fifth's area.

KC: "You asked before if I went to Guadalcanal for the 50th

anniversary of the landing. Yes, I went to Guadalcanal about four

years ago to the day. I landed on 5 July. And, yes,

I was there for the 50th anniversary celebrations, which lasted

a week. There were all kinds of ceremonies and speeches but what

I enjoyed most was meeting and talking with some of the many,

many vets who came back. That was indeed special. I think we had

four Medal of Honor winners there.

"Evidence of the war is everywhere, Mr. McConnell. If you

go into the bush, or up into the mountains, and get out to look

at something, sooner or later, some Solomon boys will appear at

the edge of a clearing. They'll shyly stand back, with something

in their hands. When you walk over to them, you'll see that what

they have in their hands is a helmet, or a bayonet, or a pineapple

grenade, or a mortar round.

"Live ordnance is everywhere and it's a really dangerous

problem. As a matter of fact, up on Bougainville, where a civil

war is raging, the rebels' main weaponry is homemade bombs made

with the cordite from W.W.II ordnance left behind.

"I was way up in the mountains one day at a place called

Gold Ridge. It's in the mountains behind (due south) of Henderson

Field. Met some Solomon men out walking. Noticed one of them wearing

dog tags. Asked him where he got them. Said he found them in the

bush near Henderson. They were U.S. Navy, from the war. If I'd

had a pen, I'd have written the guy's name down.

"The war is all around. The country's main hospital is in

Honiara, the one built after Guadalcanal was in hand and known

thereafter as the 'No. 9 Army General Hospital.' I had only been

there a few weeks and, as the Telekom Company was digging a ditch

right in the heart of Honiara, workers uncovered the remains of

two Japanese soldiers buried in a shallow grave, complete with

helmets, etc.

"Where was your unit during the battle? When I have time

this next week, I'll try to read a little about your unit's movements.

"Until later, best regards. Kent

CHAPTER THREE

Battle Discussions

JM: "My unit, 'K' Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Regiment was

in the second wave to land on Beach Red. Our regiment's initial

objective was a large mound of terrain behind and above the airstrip

and was called simply, 'grassy knoll'. We would later learn that

its official name was Mount Austen.

"We went through various degrees of hell for three days getting

there, climbing and subduing the entrenched Japs and establishing

a lookout point. (At the end of this story in the Appendix is

a poem/story about that agonizing venture. It was a poem started

on Guadalcanal in late 1942, but not completed for many, many

months.)

"Those first three days spelled out a lot of the entire story

of the Guadalcanal campaign. We experienced large doses of fear,

anxiety, near-death thoughts and encounters, punishing damage

to our bodies, extreme thirst and hunger and almost no sleep for

the entire time. I won't go into the difficulties of personal

hygiene such as cleanliness, and nature's demands. In my case,

and I'm sure in many others, we were unable to relieve our bowel

demands for the entire three days. There just were no opportunities

or convenient places for such necessities. You didn't dare wander

off from the main body of troops for fear of being killed or captured

- or worse, mistakenly shot by one of your own men!

"There were no provisions for cleaning one's self on those

occasions either. It was something that was done only when the

body would not allow any alternative. I only mention it here,

because over the years, in many stories, I have never seen it

addressed. And yet, it was a very serious problem that had many

side effects and repercussions that contributed to deteriorated

performance. Little did I know at the time, that it would set

a pattern of behavior and living that would become all too familiar

to us in the coming months.

"After securing the 'grassy knoll', which turned out to be

a fairly good sized hill, we moved downward toward the airstrip

to make sure there were no enemy soldiers or workers still entrenched

there. Fortunately, the Japs had moved out so quickly that there

was no chance for them to take along any of their food supplies

- mostly, insect-infested rice and oats. We didn't know at the

time that we were looking at a large portion of our own daily

subsistence for the next few weeks.

"From there we moved to several different areas including

our "home" for the next few weeks, where we were assigned

to beachfront positions (my battalion, - 3rd) while the other

two battalions (1st & 2nd) of the First Regiment wrapped around

and up the western banks of the Tenaru River.

"During the night of August 21, a Japanese regiment, two

thousand strong, under the command of Colonel Ichiki tried to

breach our lines along the river. The 1st & 2nd Battalions,

with artillery support from a battalion of the 11th Marine Regiment,

repulsed them and killed all but a few hundred of them that managed

to pull back and away from our lines. Though Col. Ichiki massed

several 'kamikaze' frontal assaults on our lines in a fierce determination

to break through, our men held their ground and repulsed each

wave thrown at them. The overconfident Colonel was faced with

a loss of face and total embarrassment. Rather than go on and

face his superiors, he committed hari-kiri on the morning after

his failed endeavor.

"Some spectacular pictures of the dead Jap soldiers partially

buried in the sand on the beach were taken by our Intelligence

officers and the war correspondents that were with us that later

showed up in magazines and newspapers all over the United States

in subsequent weeks.

"That spot was immediately in front of my battalion's positions

on the beachfront. The bodies had washed down the river in the

darkness into the ocean and the tide deposited them back on the

beach and partially buried them.

"During the actual engagement, my company was about 100 yards

to the left rear from the fighting, in ready reserve to fill in

if needed, which didn't happen. There would be many occasions

in the future when we were elated that our fellow regimental battalion

Marines had stood the test and held out on their own. Of course,

the situation was reversed at times, when we were the ones under

siege while our reserve battalion was heaving a sigh of relief

and giving thanks to our stalwartness.

"But imagine our surprise in the morning to see all the dead

bodies in front of us! I'll give an account of our other combat

contacts in the next email.

"So best regards, and please Kent, call me Jerry."

KC: 7/2/96:

"Okay, Jerry. I know exactly the photos you're talking about,

the ones of the dead Japanese soldiers half-buried in sand. I

know the spot, too. However, there's been some controversy about

the Tenaru and Alligator Creek. Most people (veterans and historians)

now feel that most contemporary combat references to the "Tenaru"

are actually designating Alligator Creek, a few thousand yards

west of the Tenaru. (As a matter of fact, the Tenaru River will

always hold special meaning for me: it's where I took my wife,

a Dane I met in the Solomon's, on our first date!)"

JM: 7/2/96

"Kent,

"There was also confusion when we first went in, some of

the old natives said the Tenaru was actually farther east. We

also heard it was a tributary of the Ilu River called Alligator

Creek. Captain Herbert L. Merillat who was the Division Historian

on General Vandegrift's staff, wrote a book titled simply, "The

Island" and he addresses the confusion, but states that in

his writing he used the names that were known to those Marines

that had landed there. And, yes I can see where the Tenaru would

carry special significance for you as it does for me, though God

knows, worlds of difference between the two!"

KC: "Wasn't that spot at the Tenaru mouth right across

from the infamous sand bar now known as 'Ichiki's Point'? That

was where Col. Ichiki's unit was decimated -- that may have been

the soldiers you saw the morning after (I'll have to check)."

JM: "Yes, as I described in a recent email that might

still be on its way to you, it was Col. Ichiki's troops that were

given those less than ceremonial burials and it may be known as

'Ichiki's Point' now, but back then we called it 'Hell's Point'.

"A strange thing about those bodies however, was that we

were moved back inland out of sight from the beach for several

days after the bodies were discovered and never did learn how

they disposed of them. And to be truthful, I really never wanted

to know.

"In that battle, Private Al Schmid, a machine-gunner, fought

off the Japs though blinded by a grenade explosion. Another wounded

Marine who was with Schmid and still had his sight, would tell

Al in which direction to fire the machine gun. He accounted for

a considerable number of those dead bodies all on his own. He

got the Medal of Honor for his actions on that night. A movie

starring John Garfield as Al Schmid, called, "Pride of the

Marines", was made from that story. (JM Note: Shortly after

this letter was written, I remembered that Schmid had been decorated

with the Navy Cross instead of the Medal of Honor.)"

KC: "By the way, 1st Regiment -- didn't you guys capture

Henderson Field? Right after you landed ... like within a few

days? Wasn't your unit under the command of Lt. Col. McKelvy?

And later, in October, you saw action at the Matanikau, correct?

And then, Point Cruz?"

JM: "Yes old Wild Bill McKelvy was our battalion commander

(3rd). Talk about your old "blood and guts" Marines,

there was one. He only knew one direction to go - forward. I always

wondered what he would have done if ordered to withdraw. I suspect

an adult tantrum of sorts would have been witnessed, but ultimately,

as a good Marine, he would have obeyed orders - but grudgingly.

"I as said earlier, we had been assigned to capture a high

point south of the airstrip, named only "grassy knoll"

on the crude, make-shift maps we were all given (I still have

my copy after all these years) which later was identified as Mt.

Austen. When we landed we set out immediately for that destination

and actually secured it on the third day.

"We then went down to the airstrip and I never did know if

it was planned that way or that we just happened to be the first

ones to actually arrive there. There really wasn't anything to

'capture' as all of the Japs had fled to the hills and jungles.

However, I should say that we did 'capture' some pretty good caches

of Japanese beer as well as their rice wine, called saki.

"We also found large stores of rice and oats that would later

be our main rations after the Navy ships left with more than half

of our food supplies. Other less desirable food items such as

snails, octopus, and fish-heads were also added to our food banks

by the mess sergeants where attempts to disguise them to serve

to us nearly always failed.

"And yes, we did see a lot of action at the Matanikau. The

3rd Battalion and my Company (K), was on the eastern side of the

sand bar where ten tanks tried to come across in October. Thanks

to our anti-tank weapons and the 11th Marines heavy artillery

behind us, they were stopped like ducks in a shooting gallery.

I say "thanks" because had they gotten through I'm sure

I wouldn't be writing this today.

"As though the tanks weren't daunting enough as they roared

and lumbered across the sand bar headed directly into our positions,

swarms of Jap infantrymen came along with the tanks, - along their

sides and behind them. When the tanks were stopped, the ground

troops continued to come across. There was a lot of man-to-man

action by both country's ground forces that night. There were

so many of them coming at us and screaming bone-chilling epithets,

in both English and Japanese, our five-shot ammunition clips were

soon emptied and we had to rely on our bayonets. There wasn't

time to reload a new clip of ammunition as their soldiers were

running directly at us.

"Fortunately for me, being only a bit over five foot eight

inches and down to the one-teens in weight, most of the Jap soldiers

I encountered were actually smaller. In fact, I had a height advantage

over many of them. Another advantage we had was that they also

carried single shot rifles, which quickly ran out of ammunition

as ours did. Then it became a contest of strength with the bayonets.

Our larger size, and by that time in the campaign, better feedings,

made us stronger and quicker. I always thought that it could also

have been that we were probably scared shitless while they were

ready to die for the Emperor causing careless errors.

"There were a few moments when I was certain that it would

be my last night on this beloved earth. But I was bailed out in

one instance by one of my nearby buddies with an automatic rifle

that had a fifty round clip. This memorable forever occasion occurred

when two Japs were charging at me at the same time. From somewhere

behind I heard a loud scream, "Drop, Mac" which I did

without delay. In less than a second I heard the rapid 'burp-burp-burp'

of an automatic rifle cutting down the two Japs, one of whom landed

almost on top of me. But such actions were common that night.

"We were also on the southeastern flank of 'Bloody Ridge'

the night Edson's Raiders took it on the chin in September. The

Raiders repulsed the first wave of Jap troops who then fell back

and, lucky us, decided to try to come around through our area.

"One of our Lieutenants, Joe Terzi, First Platoon Leader,

and two of his men who had been well out in front of our lines

on listening posts were unable to get back and were trapped behind

the advancing Japs when they hit our lines. We were pretty well

dug in and after their first push failed they just retreated back

to an area where Terzi and the two men were hiding. There was

only one way for Terzi to go and that was farther away from our

lines.

"For 2 or 3 days they had to lie low and eat berries and

roots and fortunately, they were on the edge of a small stream

where they could get water. Our guys were sure happy to get back

to our lines after the Japs had departed, or what was left of

them. And we were overjoyed at seeing them return unharmed, but

very hungry.

"Earlier that evening I had been on that same listening post

out in front of our lines by some twenty-five or so yards in the

grass. It wasn't the tall, razor-sharp Kunai grass, just regular

grass about twelve to eighteen inches tall. I was there with three

other guys. Actually, we were split up in two pairs of two and

separated by about twenty-five feet.

"It was nerve-wracking duty being so far away from your own

troops and probably nearer to the enemy who were masters at stealth

and quiet. You didn't dare talk or make any noises. We knew how

far we were from our front lines, but we had no idea how close

we were to their front lines. Every sniff, throat tickle, or yawn

had to be muffled to prevent detection. We sat there rigidly for

two full hours while bugs and flying insects feasted on our bodies

- or at least, the exposed parts thereof.

"I was only too happy when we heard our relief coming up

on us with the finger-snapping signal of recognition where the

middle finger is pressed against the thumb and then rubbed across

until it snaps down onto the palm. As quietly as could be there

would be two snaps, pause, two snaps, pause and two more snaps.

If the answering one snap, pause, one snap, pause, one snap wasn't

forthcoming, the relief detail would return to our front lines

and report that those of us out there had either been killed or

taken prisoner.

"On this instance, one of us was quick to return the signal

so we could get back to the relative security of our own lines

moving very slowly so as not to cause a noisy rustle of the grass.

But unfortunately, Lt. Terzi and the others mentioned before,

were the unlucky ones who got trapped behind the Japanese advance.

"It seemed only seconds after we got back to our lines and

safely in our foxholes, positioned and ready for the onslaught

of Japs, that they began to hit us. Very quietly at first which

made it seem a bit surreal and almost like a dream sequence. But

the noise of rifle fire, grenade explosions and the screaming,

and the outbound artillery fire from our heavy weapons battalion

to our rear, made us realize that we were in for some heavy combat.

"The artillery fire however, made the difference. The explosions

were quite often a bit closer than we would have preferred and

shrapnel zinged and screeched all around us, but it was hitting

the Japs dead on as they tried to penetrate our positions. As

they began to fall back the artillery followed them as though

it had eyes of its own. Actually, it literally did, only it was

in the form of our human observers who noted the positions of

the Japs and informed the artillerymen to our rear of their movements

by field telephones. The earlier quiet when their attack began

was quickly displaced by screams and shouts of orders from their

leaders to a point of what seemed like a full scale riot. Their

fallback to positions that afforded them more safety and out of

range of our small arms fire was accompanied by much appreciated

quiet with only the moans of the few of our men that had been

wounded. We luckily survived any fatalities that night.

"And then when Lt. Terzi and his men returned it gave us

more fortunate news and we seemed whole again. They had outwaited

and really, outfoxed, the Japs and were able to come back to our

lines. They told us that it was probably less than five minutes

after we had very quietly crawled back to our lines that they

heard the grass rustling to the front. The rustling got louder

and it became more obvious to them that there was a large force

of men moving toward our lines. Our men attempted to come back

to our lines but realized that some of the Japs had already come

in from the uncovered flank and were between them and our lines.

They had no choice but to move off to the opposite flank away

from the sound of the oncoming soldiers and away from the safety

of our lines. But thankfully, they were able to come back to us

later.

"The Point Cruz thing was also nearly a disaster. Our own

planes, thinking we were the enemy, started to strafe us. We quickly

laid out any white undershirts, shorts, handkerchief, etc. and

spelled out "U S" as big as we could. They got the message,

tipped their wings and went on their way. Luckily our fly-boy

guys weren't good shots that day as all they did was stir up the

dust and nick the hell out of the trees all around us. But we

must have been quite a sight all sprawled out in a disorderly

pattern, most minus all clothing, having removed our white underwear

items to make the distress sign for the planes. An enemy patrol

could have had a field day picking us off at their leisure."

KC: "Jerry, if so, it appears that Uncle David was right

near you most of the battle."

JM: "He probably was. I know the First and the Fifth weren't

usually too far apart from each other. At times even when we were

in close proximity, we couldn't make contact because of enemy

activity, but both units always knew the other was nearby. It

was probably mental telepathy. We just knew they were there and

vice versa. Field communications were used sparingly as sometimes

they would squeal loudly if not operating properly, but I'm sure

our officers were always in some form of contact with the units

that were flanking us."

KC: "A personal note. I never knew Uncle David. But his brother,

Uncle Ray, was like my father. Ray was also a Marine, in the 1st

Tank Battalion (Cape Gloucester, Good Enough Island, Peleliu).

"I grew up hearing about Uncle David. When I was a kid, I

used to gaze through family photo albums, look at his picture,

read his letters, and read his poems.

"Uncle David wrote the poem below while on Guadalcanal. He

sent it in a letter to his closest sister, my grandmother, who

raised me. I grew up carrying this poem in my heart and I've had

it copyrighted. It was one of the last things our family ever

heard from him.

"I'll share it here with you, as you can probably relate

to it. Understand: Uncle David was a sharecropper from Tennessee,

with an eighth-grade education and, who, until he joined the

Marines, had never been outside the state of Tennessee.

"Somewhere in the Solomons,

Where the sun is like a curse and each day is followed by another

slightly worse.

Where the brown-colored dust blows thicker than shifting

desert sand

and all men dream and wish for the fairer, greener land.

Somewhere in the Solomons,

Where a woman is never seen,

Where the sky is never cloudy and the grass is never green.

Where the dingies' nightly howl robs a man of his sleep,

Where there isn't any whiskey and beer is never seen.

Somewhere in the Solomons,

Where the nights are made for love,

Where the moon is like a searchlight and the

southern cross above

sparkles like a diamond on a balmy tropic night,

it's a shameful waste of beauty when there's not a

girl in sight.

Somewhere in the Solomons,

Where the mail is always late,

Where a Christmas card in April is considered up to date,

Where we never have a payday, never have a cent,

but we never miss the money cause we'd never get it spent.

Somewhere in the Solomons,

Where the ants and lizards play,

and a thousand fresh mosquitoes replace each one you slay...

So come on, you Fifth Marines and throw out your chest,

For you have completed your mission well ahead of the rest.

So take me back to 'Frisco, let me hear the Mission bells,

For this God-forsaken island is a substitute

for Hell.

PFC David King Massey, USMC

Guadalcanal

November 9, 1942"

JM: "What a great poem! One would never know that the writer

had only an eighth grade education, it really is very well done;

and what a great coincidence (or perhaps not, there may have been

lots of others) because I wrote my first poem on the 'Canal also.

It was not nearly as well structured as David's, but it carried

a similar message.

"I wrote a second one which detailed the horrors of the trek

to Mt. Austen after we had landed at Beach Red. I titled it "The

Grassy Knoll." I didn't finish it before I left and I don't

recall how long it was before I did, but it and the other had

remained tucked away for many, many years until a few years ago

when the country became aware of the 50th anniversary of W.W.II.

"With so many reporters interviewing and local schools doing

veterans programs the self-imposed gag that I had put on my memories

of that place suddenly came off and it was like a burden had been

lifted or a door had been opened and a fresh breeze blew through.

I'll tell you more about this and the poems another time."

KC: "I just wish young kids today just had a clue about what

men like you went through to keep us free. When you guys landed

on August 7th, by all accounts, we were losing ground to the Japanese

juggernaut coming down the Pacific towards the grand prize of

Australia. You're right: Guadalcanal was the first offensive land

action of the Pacific theater. It was the first time we took the

initiative to them and fought back.

"Before Guadalcanal, strategic points in the Pacific fell

like ripe fruit into the hands of the Japanese: the Philippines,

Formosa, Wake Island, Hong Kong, Burma, Siam, SE Asia, Malaya,

Singapore, New Guinea. If allowed to finish the airfield on Guadalcanal,

the Japanese could strike directly at Australia.

"As a matter of fact, Australian leaders had already conceded

the northeastern territory (now Queensland) defenseless in the

north, they drew the line at Brisbane and resolved to defend their

homeland there. MacArthur convinced them to concede nothing.

"Yes, Guadalcanal -- by any objective measure -- was the

turning point in the war for the Allies. And when men like Bull

Halsey and Chesty Puller replaced men like Frank Jack Fletcher

and Ghormley, we started taking the war to the Japanese.

"Enough. Hope you enjoy the poem. I have a photocopy of Manchester's

Op-Ed; if you want, I can fax it to you. Until later. Kent"

JM: "I'm not set up to receive faxes, but I would definitely

like a copy of his article. Could you mail it to me? I would appreciate

it very much. The Grassy Knoll poem is quite lengthy, but I'll

mail you a copy if you'd like it. Jerry"

KC: 7/2/96

"Have you written all this stuff down anywhere, Jerry? You

are, as they say, an eyewitness to history. You should make every

effort to preserve your recollections. A hundred years from now,

people will read it -- even if it's just your family -- and wonder,

just as I did as I read Civil War soldiers' accounts when I was

growing up. It matters, Jerry. What you and every other man

went through back then matters a great deal. I urge you to write

it all down."

Chapters

4-6